Joe and Eileen Backofen visited the grave of Eileen's grandfather,

Gregory Dupkanich, during a trip to the Slovak Republic while she was researching her family's history.

| Laker Weekly | smithmountainlake.com | Laker Media Vol. 2 No.35 | Friday, July 10, 2009 |

Eileen Backofen always thought she came from nowhere. She was born in Brooklyn, N.Y., and spent most of her childhood there. And most summers were spent in Forest City, Pa., her parents' hometown.

Shortly after college, Backofen and husband Joe moved to Northern Virginia in 1983, where she taught in the public school system for 24 years. And she and Joe lived in Moneta part time from 1995 until retiring and moving to the lake full time in 2007.

But that's Backofen's personal history. Her family history stopped abruptly with her grandparents: a woman who spoke little English and a man who died before Backofen was born.

After an extensive search for her roots, it turned out she was right all along. She really was from nowhere.

Joe and Eileen Backofen visited the grave of Eileen's grandfather, Gregory Dupkanich, during a trip to the Slovak Republic while she was researching her family's history. |

|

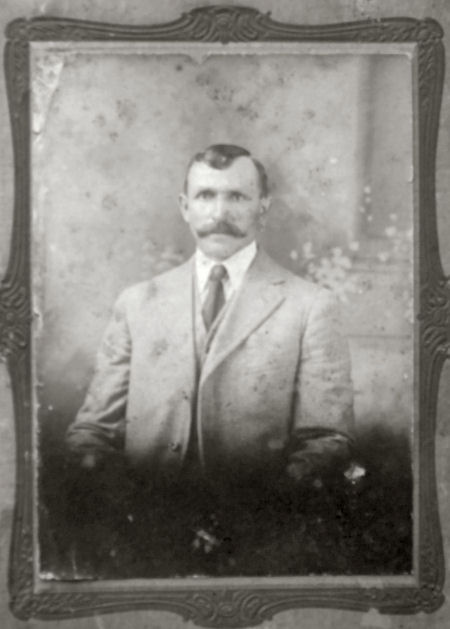

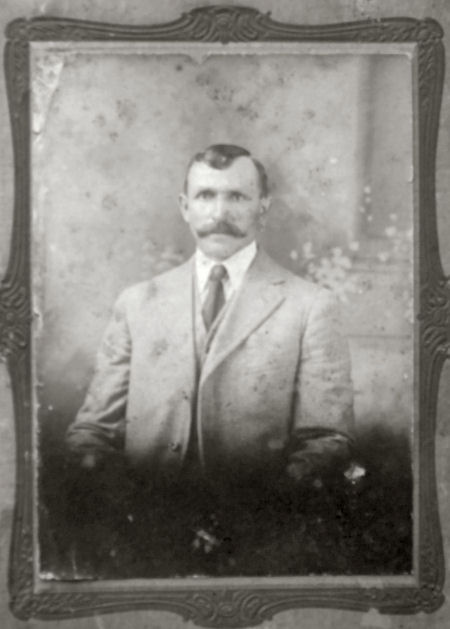

Gregory Dupkanich, pictured at age 30. |

|

|

|

| Eileen and Joe Backofen (center) met with several of Eileen's relatives in the Slovak Republic in 2008 after a years-long search for her family's roots. | The view of Sambron, where Eileen Backofen's grandmother was born, from the cemetary. |

Tangled roots

Backofen's interest in her heritage began at a young age. At 10, she would sit and talk with her grandmother, Katarina Korshnak, who immigrated to the United States in 1900 at age 17.

"She didn't speak much English, even though she had been here almost 60 years," said Backofen. "But I had learned to speak Slovak reasonably well."

Or at least she thought what she was speaking was Slovak.

She also thought Korshnak was from Schonbrunn, which is located in Austria.

Wrong again.

Then there was her grandfather, Gregory Dupkanich. Backofen's problems researching information about him began with his name. It had been spelled incorrectly at Ellis Island, N.Y., when he immigrated to the United States. And it was spelled differently, but also incorrectly, on his marriage license to Korshnak.

The only thing Backofen knew for sure was that Dupkanich and Korshnak were both widowers when they married. Together, they had one child, Backofen's mother.

But Dupkanich had another family "back in the old country." Occasionally, he would cross the ocean to spend several months with his two sons and grandchildren. And in 1935, he died there.

"I never knew him," said Backofen. "I'd never even seen his picture."

A breakthrough

One day, Backofen's mother stumbled across some documents. One was Backofen's grandmother's baptismal certificate from Sambron, Slovakia.

It was then that Backofen realized her phonetic translation of the village was wrong. She had been further confused because Slovakia was under Austro-Hungarian rule during her grandmother's lifetime.

"No wonder I couldn't find her," said Backofen. "I was looking in the wrong country."

The discoveries kept coming. With the advent of the Internet and with new documents and search tools being added every day, her search became easier.

As Backofen was looking for her grandfather through obituaries posted online in 2006, her mother struck gold: Among a pile of family documents was Dupkanich's death certificate.

"That was the big thing," said Backofen. "Now I know where he died."

The village was Habura, which is about 85 miles from Sambron.

Armed with the names of both villages, Backofen was able to find her grandparents through an online search of Ellis Island immigration books. That's when Backofen found that her family was closer than she thought.

Turns out one of her grandfather's two sons had immigrated to the United States. He changed his last name to Duker, settled in Pennsylvania and had six children. One of them was serving as a priest in a Greek Catholic church in Pittsburgh. Backofen summoned up the courage to call her cousin.

"I said, 'I believe we have the same grandfather,' " she said. "We wound up talking for two hours."

Msgr. Duker still kept in touch with the cousins in Slovakia. By the time they hung up, Backofen had their addresses.

Going home

With the pieces finally in place, Backofen and her husband Joe decided to make the trip to Slovakia last year. They booked a cruise on the Danube River and planned to rent a car at the end and drive through the countryside to the villages from which Backofen's grandparents emigrated.

But they knew language would be a barrier, as most Slovak villagers speak little to no English.

"I used to be able to understand my grandmother," said Backofen. "So I got CDs and books and said I'm going to learn again."

When she was sure her grasp of the language would suffice, she penned a letter, in Slavic, to two of her cousins. Just in case, she attached an English translation.

"The first thing they did when they got their letters was call the priest [Msgr. Duker]," said Backofen.

Once they knew she was for real, the cousins who'd never met arranged a meeting.

Family ties

The Backofens' cruise had a stopover in Bratislava, where two cousins awaited their arrival at the dock. There were hugs, tears, family history and gifts exchanged.

One cousin gave Backofen a book titled "The People from Nowhere: An Illustrated History of Carpatho-Rusyns." It detailed the small subsect that was all but forgotten because of World War II and the Communist takeover of the Austrian-Hungarian Empire. It was the history of Backofen's people.

"No wonder I couldn't find myself," said Backofen. "I'm from nowhere."

But the greatest gift exchanged at their meeting was a photo of Dupkanich, taken when he was about 30 years old and living in America. Backofen cried.

"I've never seen a picture of my grandfather," she said. "It was just amazing."

The day ended too soon and the Backofens returned to their cruise ship. Two days later, they hit the countryside in a rented Ford Focus, heading for Medzilaborce. It was there that Backofen met her cousin, Pavel, who had more history to share.

He explained that Backofen's grandmother had been speaking Rusyn, a Slovak dialect.

"That was why so many of the words I remember hearing from my grandmother weren't in my Slovak dictionary," said Backofen.

The following day, Pavel led them to Habura to the homestead, more family and Dupkanich's grave.

"Not only was it nice, it's right up next to the priest's," said Backofen. "He was somebody important in that village."

His tombstone inscription was in Cyrillic, which Backofen learned was a nod to his importance.

"It was because he was a Rusyn patriot," she said. "He was leading the resistance against the Czech Republic. ... He wanted to retain the Rutherian heritage."

But Backofen had only one day to spend in Habura before they were off to Sambron. There was no family there, but a villager showed Backofen records in the town office detailing when Backofen's grandmother had left for America. Most importantly, Backofen was able to walk the grounds of her ancestors.

Rooted in family

Since Backofen's visit, she has exchanged cards with her cousins. But her handle of the Slovak language has dissipated from lack of use.

"They called me at Christmas and I was so surprised, I couldn't say a word," said Backofen. "I forgot the Slovak language."

But she may get her chance to practice again. The Backofens would like to go back for another visit.

"If the stock market goes up, we'll go," said Joe Backofen.

Or not. Eileen Backofen has other roots to dig up, these on her father's side of the family.

"My father was Lithuanian," she said. "I have some research to do there. Who knows, I may go find that village."

For more information about Eileen Backofen's quest to find her roots, visit www.brigs.us/portfolio.

LAURIE EDWARDS | Laker Weekly 721.4675 (ext. 406)